By Phil Mackintosh, Chief Economist, Nasdaq

Data shows that since the turn of the millennium, stock splits have become decidedly unpopular.

Back when humans had to calculate indexes by hand, the Dow was built to include one share of each ticker. That meant all you had to do was add up share prices and you had your index. That also seemed to encourage companies to keep their stock prices closer to “optimal” trading levels, which we’ve shown seems to happen when the stock naturally trades between one and two ticks wide.

Like what you see? Click here to sign up for Trader Magazine’s weekly newsletter to get breaking news, exclusive features, the industry photo of the day and more.

Stock splits have become unpopular as markets have automated.

Data shows that since the turn of the millennium, stock splits have become decidedly unpopular.

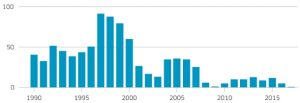

Back in the 90’s it wasn’t uncommon for 50 stocks (or 10%) of the S&P 500 to split (Chart 1). This helped keep stocks in a relatively consistent price range (Chart 2) which in turn maintained more consistent tradability characteristics across the index.

However, since the credit crisis the number of stock splits per-year has been closer to 10, just 2% of all tickers per year, despite the index rising more than 200%, which would triple the price of an average un-split stock.

Chart 1: Number of stock splits annually by S&P 500 companies

Average stock prices have risen as stock splits have declined

Not surprisingly, the lack of stock splits has caused average stock prices to rise.

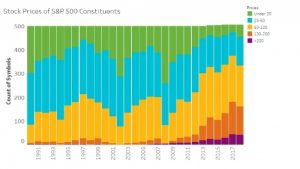

These days around one-third of S&P 500 companies are over $100 per share—a level where we’ve shown that even the most liquid stocks start to trade more than one tick wide.

In fact, the simple average of stock prices is now around $100 per share, thanks in part to 5 stocks trading over $1,000 per share. However those high priced stocks also need to trade fewer shares to trade the same value, which tends to reduce their ADV for the same notional liquidity. As a result the trade weighted average price:

Chart 2: Almost one third of S&P 500 companies today have prices over $100 per share

Source: Nasdaq Economic Research

It’s also interesting to see the change in composition of the S&P500. Back in 1990:

Chart 3: Change in price composition of the S&P 500

Source: Nasdaq Economic Research

For traders, this is important. As we have shown in many recent posts, the one-size-fits-all rules of Reg NMS affects tradability of stocks:

For portfolio managers and brokers it also distorts commission allocations. Although because brokers bundle commissions, investors don’t see the economic cross-subsidy given to support research and trading in the highest priced stocks, because commission spend is based on all shares traded.

Although high-priced stocks might look good to management, they aren’t great for investors. That’s because they cause a whole lot of distortions, from limiting the ability to allocate stock compensation, to increasing the risk of a single round lots or options contract, increasing costs for investors and distorting trading economics for brokers. To address the trading issues, we’ve called for intelligent ticks in TotalMarkets, but an even better solution is right-sizing stock prices.