Liquidity struggles are a global problem, but in the Australian equity market the issue is even more acute. A small investable universe, increasing fragmentation and the worldwide lean into shorter settlement cycles are only adding more pressure, squeezing at-touch liquidity to a concerning degree.

“Australia is one of the most fragmented markets in Asia,” observes Dylan Kluth, head of equities trading for APAC at Macquarie Asset Management. The rise of alternative trading venues and strategies is chipping away at at-touch liquidity, dark pools, algorithmic products and more weakening what is already a small market.

Like a snake eating its own tail, the more these services are embraced the more liquidity shrinks – and the more attractive non-traditional routes become. “It’s probably accelerated that block component; if you actually want to do something, you need to engage a broker and have a conversation around where you’re positioned and what you’re interested in,” Dion Cooney, APAC head of trading at AllianceBernstein, explains.

Going global

“The investable universe is really quite small; there’s an ASX 300 index, but really you’re investing in 200 or less. The bottom tier, by market cap, is hard for a global manager to get down to. That’s where some of the liquidity concerns come from,” Cooney says.

Banks and resources take up most of the market, with other sectors taking a back seat. The region also lacks the technology appeal that so many investors are seeking, with super funds – Australian employer-sponsored pension schemes – pushing investment out to the US rather than funding domestic companies.

Domestically, “the bulk of the market is made up of institutional money”, says Cooney. “The big players are now super funds. They were previously externally managed, but the majority of them have brought money in house. Then you’ve got the passives, actives, domestics, and international players.”

“20 years ago you would have seen Aussie super funds investing in Aussie markets. Now, that pool has gotten larger, there’s a lot more offshore investment from them,” says Cooney. In spite of growing interest, though, the market is limited.

A changing landscape

Over the last 10 years, the Australian market has changed dramatically. “Average trade sizes have increased over the past decade,” Kate Weidenhofer, head of Australia at Liquidnet, says, “driven by the rise of block trades and the standardisation of minimum execution quantities. These are designed to counteract high-frequency trading and minimise signalling risks.”

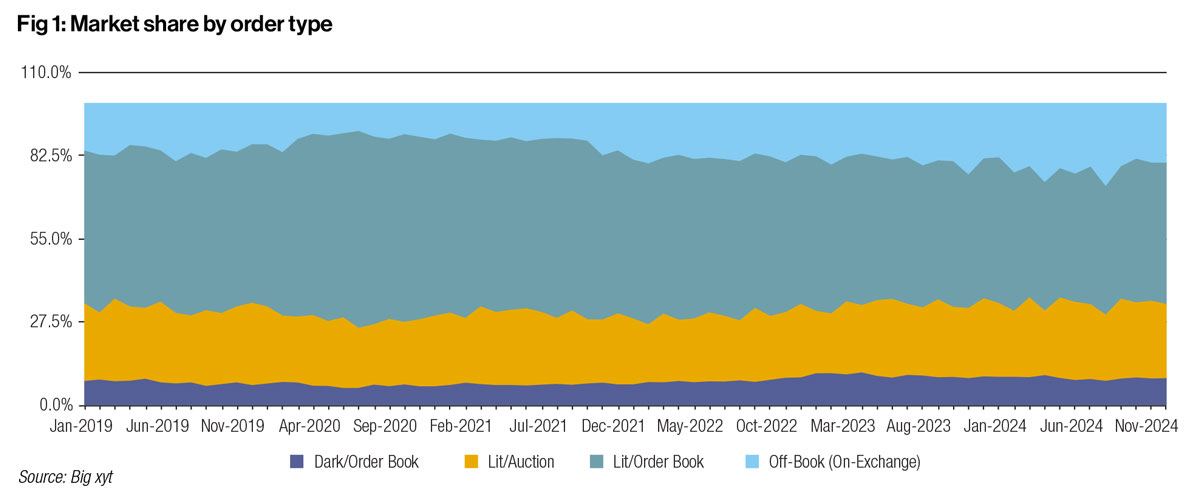

The rise of block trades, as illustrated by the increased market share of off-book/on-exchange or off-book large in scale/negotiated trades, has led to a new kind of desk in the region, Cooney notes.“A raft of brokers have formed what they call high-touch block desks – building on fragmentation even further. Traditional high-touch orders are still being serviced by a high-touch trader, but if it goes over a certain size it’s sent to a group within the broker firm that only trades block-type orders.” In 2024, off-book on-exchange market share has repeatedly exceeded that of lit/auction trading, according to data from Big xyt (see Fig 1).

Some of the largest of these desks are run by UBS, JP Morgan and boutique investment bank Barrenjoey, all of which were unwilling to speak to Global Trading about the impact their strategies are having on liquidity.

“The buy-side is navigating Australia’s fragmented and concentrated equities market with a multi-faceted approach,” Weidenhofer says. “There’s a growing emphasis on leveraging committed Indications of Interest (IOIs). At the same time, aggregators have become essential tools for consolidating liquidity across the fragmented landscape.”

As traders try to avoid information leakage and frontrunning and access hidden liquidity, dark pools have become an increasingly popular approach. From concerns about predatory behaviour in execution to the growth of algorithmic products, a greater number of traders are opting to avoid the lit market.

“Dark pools now account for over 26% of value traded as of Q3 2024, reflecting their growing role in the ecosystem,” Weidenhofer observes, citing Liquidnet data. ASX Centre Point and Cboe run the most popular of these venues in the region. The anonymous trading of large blocks, matching traders with counterparties while minimising market impact, is an appealing prospect. However, it is slowly drawing flow away from lit markets.

Another way to improve the matching process is through conditional orders, whereby traders can post an indication of interest across multiple venues at once. The introduction of these order types has been a significant development in Australia and the wider APAC region, Cooney says. With this approach, traders are able to rest full orders in multiple venues and firm-up requests once a match is found. This allows larger trades to be completed with minimal information leakage, and removes the need to split orders. Being able to access numerous venues at once improves liquidity access in fragmented markets, and cuts down how long it takes to complete a trade. Along with dark pools, these tools open the door to hidden natural liquidity and enable trades to take place with minimal market impact.

One such platform is Cboe BIDS, which was launched in Australia last year following a successful rollout in Europe, the US and Canada. “Getting that universe of investors up so you have more matches is a major development,” Cooney states. “[Cboe BIDS] does have some different functionality to other electronic block matching, where you’re only allowed to execute in their pool with their broker. This is broker-agnostic, so you can choose your own executing counterparty. That benefits the buy side.”

However, slowly drawing flow away from lit markets is doing nothing to help dwindling visible liquidity, which is essential for price formation. “That [algorithmic] flow feeds on itself,” Cooney notes. Despite the benefits, more trading in the dark means more opaque markets – something regulators and market participants alike want to avoid.

An open and shut case?

As has been seen in the US and Europe, liquidity is increasingly moving towards the close as passive investing and ETFs gain popularity. “A decade, maybe 15 years ago, that liquidity would have been nearer 5-10% at the open and probably 10-15% at the close. It’s now less than 5% at the open and nearer 25-30% to close,” Cooney observed of Australian markets.

This shift is in part due to geography. “There are a lot of developed Asian markets open at the end of the day, so there’s more opportunity to generate trading ideas and liquidity at that time,” Cooney explains. “It makes sense that it would be backloaded.” The same thing is happening in Europe as it adjusts to suit US market hours. “It’s something that local traders and buy-side investors have had to get used to,” he says.

In April of this year, ASX published plans to remove staggered opening times for cash products. This was broadly supported by an industry already accustomed to a single opening time, Australia being the last exchange to operate an opening stagger, and keen to align with global exchanges, simplify the open and reduce the window of volatility. As part of mandatory changes, this capability is live in the ASX’s Customer Development Environments (CDE+) for testing.

However, with the role of the opening auction diminishing each year, “we anticipate there will be little impact to the open besides bringing the exchange in line with global peers,” Weidenhofer says. Rather than innovative, this late market structure amendment is unlikely to make a difference this late in the day.

Kluth suggested that the inclusion of a trade at last session, which is also live in CDE+, could be more helpful in boosting liquidity. Taking place after the closing auction, this would allow traders to fill orders that were not matched earlier in the day.

T+1

Timing issues have only been exacerbated by the introduction of T+1 in Canada, the US, India and more over recent years. “The influence of the US’s move on funding trades, around the globe and within Australia, is going to be a hurdle that funds look to navigate more in 2025. While you may be able to trade, you may not be able to get money in place because of custodians or down-the-chain events that don’t allow you to take advantage of some trading opportunities that may develop. Workflows become more important,” Cooney says.

Given the country’s isolation from other jurisdictions, a consultation paper earlier this year noted that moving to T+1 is a market priority. However, the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) is already grappling with a long drawn-out settlement project: replacing its CHESS system, which recently entered its second phase after an embarrassing US$170 million failure in 2022. The same consultation paper warned against embarking on the two initiatives in tandem, with CHESS replacement the more urgent matter.

“There’s potential for a change in settlement in Australia, but that’s going to be a while out,” Cooney comments. “Not because it can’t be done technically, but I don’t think all of the steps in the chain have evolved fast enough.”

Getting moving

Kluth is quick to point out the importance of keeping up to date with emerging technology in equities markets. From transaction cost analysis to new algorithms and different applications of automation, “we continually analyse our methods for trading to identify any opportunities for improvement”, he says. In a competitive environment, and one in which liquidity can be difficult to source, this is essential.

This can include an element of trading alpha for buy side trading desks. “More and more, we are building ways to be liquidity providers instead of liquidity takers,” Kluth observes. “Our role as conduit to the market for our clients and stakeholders continues to build on the requirements of our role. That includes working with our brokers to incorporate the latest algorithmic developments into our wheel, finding more automated ways to consume our brokers indications of interest, and incorporating the full life cycle of a trade from idea to implementation.”

While the Australian market may not be the most cutting-edge, it is slowly catching up with the rest of the world and introducing its own solutions. As global markets continue to make big changes, technology development accelerates and investor demands evolve, it is not enough to lag behind global leaders. Australian equity markets need to forge their own way to remain competitive and ensure that liquidity is accessible, however the landscape continues to develop.

©Markets Media Europe 2024