Companies are demanding more flexibility in share buybacks, and banks are tweaking their products in response.

The basic premise of a buyback is simple – to repurchase as many shares as possible with a given sum of cash, and thereby reduce the issuer’s capital, boosting its earnings-per-share ratio. The market is huge. S&P 500 issuers repurchased $877 billion in the 12 months to June 2024, while European issuers purchased around €200 billion over the same period.

This generates billions in trading revenues for leading banks, using strategies where banks are rewarded for maximising share purchases below an average-price benchmark. It is a truism in finance that incentives deliver the best performance, but in share buybacks, this can sometimes be a distraction.

A case in point is UK-listed education software company Pearson, which has now shifted away from a pure performance-based model to an element of fixed fees, in conjunction with its broker Citi. To understand why, we need to explore the context behind buybacks, starting with the more mature US market.

To prevent market abuse, venues impose restrictions on companies trading in their own stock, including volume restrictions to stop them from distorting the market.

To allow buybacks, regulators have carved out special ‘safe harbour’ exemptions. In the US, the Securities and Exchange Commission has rule 10b-51, allowing brokers to buy back stock for their corporate clients during pre-earnings blackout periods. “You put it in place ahead of time, and the bank is executing this for you”, says Bruce Edlund, assistant treasurer at Cloud Software Group, which was formerly the Nasdaq-listed Citrix Systems, before being taken private in 2022. “It’s out of your control at that point”.

In Europe, the Market Abuse Regulations apply to both the EU and UK, along with exchange listing rules, which are even stricter than the US. “Companies need to be an exchange member to buy shares, so they go to a broker and ask them to buy their shares on the exchange”, explains a London-based banker familiar with the market.

Dark venues are banned, the banker adds. “Even on those permitted venues, you have to buy it through the order book electronically, and then the price that you buy at is also governed by the rules, so that corporates shouldn’t be seen as impacting their own share price”.

Choosing a strategy

The most obvious buyback strategy is the simplest. “You could just go in the open market”, Edlund says. “Just tell your banks, buy back 50 million, 100 million”. In practice, few companies follow this strategy.

One reason might be that the legally-enshrined role for banks and brokers lets them influence the choice of execution strategy. The way treasurers put it, being locked into a conversation about execution with their brokers narrows the focus to buying shares at the lowest price – using a product sold by the bank.

“The banks have all kinds of products that they love to sell you”, Edlund says, noting that their incentives are not always aligned with the client. “They make almost nothing on the open market, because everybody can do that and it’s very low cost there. They can’t really hide a big fee in there, right? Because you can check what the price was every day”.

The argument for more complex products starts from the need to maximise performance. “Most companies track the average price at which they repurchased shares during a quarter”, says Edlund, at which point, brokers offer to beat this average benchmark. “They’re making fees on that, but it should be ‘better’ than what you would have done in just straight open market purchases”, Edlund explains.

Arguably not, according to Michael Seigne, founder of Candor Partners, which provides consulting services on buyback execution. Seigne spent 22 years at Goldman Sachs, including senior equity execution roles, and believes the products that dominate the market are fundamentally flawed. “Share buybacks present a unique sent of conflicts that often go unnoticed”, he says.

Whatever the motivations, the most popular strategy recommended by brokers involves more complexity and less transparency. “The banks have different names for these”, notes Edlund, “but they’re essentially discount to average programs”.

This is usually defined as the average of daily volume-weighted average prices or VWAP during a pre-agreed time period. In effect, the banks bid to beat this unknown benchmark by offering companies a discount. Todd Yoder, CFO of construction firm S&B USA, who was responsible for billions of dollars in share buybacks at his previous companies, explains.

“You let the banks compete on the spread to VWAP”, he says. “Once you established parameters around the notional spend amount and period of time, banks bid a basis point spread discount to the VWAP. One bank says we’ll pay you five and for another it’s 10”.

Since the budget is fixed – the amount of dollars allocated to the buyback by the company – the unknown quantities are the number of shares that get purchased and the time it takes the broker to complete the purchase. As Yoder says, “It’s figuring out what size and what time horizon you’re going to target”.

The magic ingredient

The way banks do this lies at the heart of the buyback market. They compete to buy the largest number of shares at the lowest price, and to provide that competitive discount, banks require a magic ingredient: volatility.

“The bank is taking a position as an organisation on the underlying stock’s trading volatility, similar to a derivative”, a banker explains. “You should be able to generate a discount because the share price moves, and it allows banks to pick the best time to buy and the corporates to get the best share price without knowing what the future is going to hold”.

Seigne is a lone critic of this whole process, arguing that the average of daily VWAP is a ‘bogus benchmark’. It’s flawed, he says, because the nature of the averaging process allows the broker to game the benchmark, regardless of performance. The products, he says “are designed to allow the executing broker to get long the issuer’s volatility cheaply”.

Treasurers and CFOs confirm that volatility is central to the conversation. “They’ll come in, the broker’s quant people, and they’ll look at the daily volatility of your stock” recalls Edlund. “And for them, the more volatile, the better”.

Yoder explains how this quasi-derivative works. “You’re selling volatility to the banks and the more volatile the stock is, the more of a discount you can get to the VWAP”.

Volatility helps the banks because dips in the share price give them a chance to buy stock for the company at below the agreed discount price – letting them pocket the difference. But there’s a risk for the banks, as a banker points out.

“We often have instances where we have given our clients a guarantee, and we write them a check if we are unable to meet that guarantee. We do lose money. That’s just the nature of how the business operates”. According to this banker, only seven out of ten guaranteed discount buyback transactions are profitable for brokers, on average.

Dynamic hedging

Quite understandably, the bank trading desks buy hedges to limit these risks. “They’re trying to beat that benchmark”, Yoder comments. “When they do their strategy right, they’re going to put on different positions to protect themselves, right? They will probably collar it so the trade doesn’t get away from them.”

Bankers are keen to address the perception among treasurers that the pace of buybacks is connected to the trading desk’s choice of hedging strategy. “Hedging has nothing to do with what we are buying for the client, it’s not impacting our trading decision”, one says. “That hedge could be a number of different things – we could trade options in those shares”.

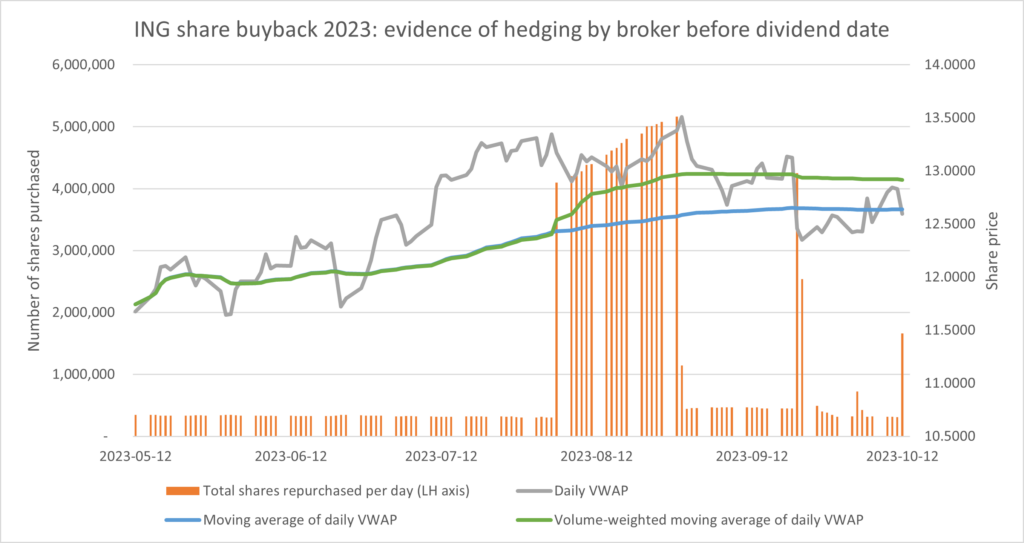

Brokers can also hedge using dividends. Seigne highlights the example of Dutch banking group ING, which between May and October 2023 spent €1.5 billion on buybacks, during which time its share price rallied. According to disclosures, the unnamed broker paid an additional €66 million in shares to ING “due to performance arrangements”. Yet, in reality, the broker didn’t lose this money, because of another factor – the ability to hedge.

According to Seigne, there is indirect evidence for hedging in the €1.5 billion ING buyback transaction. Regulatory disclosures suggest that the broker didn’t transfer the majority of the shares to ING until after the company paid a dividend in August 2023. Seigne believes that the broker did this because it prior to that date it was holding the shares as a hedge, enabling it to receive the dividend, which outweighed the €66 million contractual loss on its buyback contract.

“You could hedge that way”, a banker concedes. “But from a simple trading strategy perspective, it’s always better to buy the shares after the dividend, because when the dividend is paid, the share price drops”.

For Seigne, the race by brokers to complete buybacks on share price dips is a symptom of the flaws in the VWAP ‘bogus’ benchmark. If the average of VWAPs was volume weighted, then heavy buying at low prices would lower the average used in the benchmark, reducing the broker’s profits and hence their incentive to trade in such a way.

Whatever the processes used by banks to handle buybacks, the bursts and pauses in trading volume can be alarming for their clients.

Consider the multiple priorities that corporate finance teams have to juggle. They have to manage the company’s cash, while preparing for regular earnings calls where management will be quizzed by analysts. Meanwhile, unexpected events ranging from M&A deals to external shocks have potential to trigger large moves in the company’s share price.

Volatility may be helpful to banks in executing a discounted VWAP buyback, but is perceived quite differently by their clients. “If there are some peaks and troughs, then they’ll go hell for leather in the troughs, and you’ll see very little activity in the peaks”, according to a treasurer at a UK-listed company. “It’s a little bit difficult to manage, because from a cash flow perspective, we’ve had situations where some weeks there’d be literally no trading, and then other weeks where it would be 100 million. If you had a choice about how you structure things, you probably wouldn’t go for that.”

This race by the broker to complete the repurchase at the lowest price also conflicts with a more fundamental reason that the company engages in a buyback in the first place: signalling to shareholders, which is particularly important around the time of corporate results. “What you don’t really want to be doing is going into a results announcement where the share price has dropped a bit, and you’re no longer buying shares”, the UK treasurer says.

It’s a delicate subject because of the listing rules that force them to outsource buyback execution to a broker. But clearly, companies want to keep some influence.

Locked in

Even worse from the issuer perspective, the irrevocability of discounted VWAP deals clashes with significant events where the company ought to stop buying back shares completely. According to the UK treasurer, “No one goes into a share buyback expecting to cancel it. But at the same time, sometimes things happen”.

M&A deals are an example, adds the UK treasurer. “If you’re running a 12-month buyback programme, you’ve handed over the keys, a major acquisition pops up halfway through that process – do you really want to be carrying on, buying hell for leather, locked onto this roller coaster?”

In April 2020, the onset of the Covid pandemic abruptly changed the perspective of many UK companies from handing out cash to trying to preserve capital, making buybacks an unwelcome distraction, At this time, Diageo, BP, GSK, Unilever, Shell and Pearson all paused or cancelled share buybacks collectively worth tens of billions of pounds.

But for the broker, cancelling a buyback means unwinding the portfolio that has been accumulated by its trading desk – and this can be expensive when markets are volatile, as these companies all learned the hard way. According to a banker: “Whenever a client wants to amend any contract, the contract is amended at fair value. You terminate a transaction at its fair value.”

Such unwelcome experiences prompted Pearson to propose a completely different form of buyback contract. Rather than pay its broker, Citi, entirely through outperformance when repurchasing shares at a discount to VWAP, Pearson introduced a fixed fee element. This new arrangement also precludes hedging by Citi that could incur mark-to-market unwind costs, according to people familiar with the deal.

“Pearson has been a long-standing client of ours since 2017 and we have executed a number of buybacks for them”, Ali Farhan, Director of Strategic Equity Solutions at Citi told Global Trading. “In this instance, they wanted the flexibility to override the purchase instruction or to be able cancel the buyback. So we designed for that, and we structured it such that it’s a combination of a performance-based, how well we perform in the absence of any overriding factor, and fixed fee structure, in the event there is an overriding factor that prevents us from making trading decisions in relation to the buyback as we otherwise would”.

Farhan adds that since being pioneered with Pearson, the structure has been used by other Citi clients as well. He notes that it is part of a trend for shorter-term, more flexible buybacks. “Since COVID, we’ve seen more buybacks run on a quarterly basis, which are shorter-dated programs than before. It’s a lot easier for companies to take a three-to-six-month view rather than take a 12 month or two-year view”.

The disclosure problem

For buyside traders that buy or sell on behalf of portfolio managers, information leakage is a constant concern, leading them to carefully plan execution strategies in order to minimise it. There’s a debate among CFOs and corporate treasurers about how important this is for buybacks.

Yoder provides a US perspective. “Companies generally announce the board approval of a dollar amount for share repurchases, but the timing of the share repurchase is unknown to the public” he explains. “There is some leakage, but generally there is a lot of noise impacting share price outside of announcing the board approval of a share repurchase notional amount”.

There is less rosy view in Europe where treasurers are bound by market abuse regulations to disclose buybacks ahead of time, and report transactions on a daily basis.

“You’re always forced, by regulation, to be super transparent about what exactly you’re doing” complains a UK treasurer. “You’re disclosing every single day that this has been traded. If someone wanted to take the other side, there are opportunities for people to make money out of that”.

Examples are easy to find. In May 2024, Morgan Stanley distributed a ‘sales and trading commentary’ to clients, proposing investing in what it called a ‘forward-looking buyback basket’. The customised basket contained 62 EU-listed stocks which were expected to buy back the highest amount of their market cap over a three-month period.

Such client notes appear to show that corporate regulatory disclosures can be legitimately reversed-engineered into investment products. In submissions to the UK Financial Conduct Authority, Seigne argues for rules to be changed to conform to the US model, where trades are disclosed quarterly.

Meanwhile, attempts to introduce UK or Europe-style disclosure in the US have floundered. When the Securities & Exchange Commission proposed daily reporting on US buybacks in 2023, it was thrown out by the appeals court, after which the SEC abandoned the idea.

Bankers downplay concerns that hedge funds could be front-running buyback transactions. They claim that brokers have learned how to keep transactions sufficiently anonymous. “How we execute buybacks now, we are just another order on the exchange”, says one. “A hedge fund wouldn’t be able to tell which order is our order. So it’s not correct to say that a hedge fund is trading against the other side of the buyback”.

©Markets Media Europe 2024